The Plane Crash That Changed me

No one died, but getting trapped in an out-of-control airplane has lasting effects

Trigger warnings: The story of a plane crash; unsettling but nothing graphic.

Mention of sexual assault.

The snowstorm howled as we waited on the tarmac to board the US Airways plane at a small rural airport.

In front of me was the captain of our university’s Division I tennis team, a calm Midwesterner heading home to Chicago for the holidays. Amy told me friends of hers were staying behind for the night. “The rugby guys are having a party,” she shrugged. “I could’ve been there.”*

I told her I had a crush staying behind myself, and wouldn’t have minded delaying winter break. But it was time to get home.

I blinked snowflakes out of my eyelashes and asked the captain waiting at the bottom of the stairs, “You sure we should fly? This weather’s not looking too good...”

He cocked his head toward the door. Get on.

It was circa 1990,** and I was just a girl, so my concerns were quickly dispensed with. My discomfort fell short of straight-up foreboding, so I climbed the stairs with “American Pie” playing in my head. La Bamba was one of my favorite movies in high school. Its melancholic, doomed airplane scene depicting the day the music died haunted me long before I boarded my own prop plane in the snow.

In that scene, music legends yell over the wind and pull their coats tighter around them. Buddy Holly flips a coin, and Ritchie Valens “wins” the toss to take the flight to the next stop on their tour. When they’re nestled in their seats watching snow pelting the windows, Holly turns back to say to Valens,

Hey, relax, man. Everything’s cool. Besides, the sky belongs to the stars, right?

I boarded behind Amy, and we sat together at the front of the aircraft, and I watched snow sticking to the window. I buckled up, ready to get home to Boston. Christmas was coming.

Last weekend, decades after my crash, I finally hunted down details about what happened that night. There were things I never knew, because I ran away from that plane and never looked back, and no one ever followed up. Not US Airways, not the NTSB. I decided it was time to find out more.

It was this journey, the one where I write regularly about sexual assault and the airline industry, that pushed me there.

Listening to the women American Airlines Flight 587 F.O. Sten Molin and other predators traumatized has whipped up my own issues like a tornado in a sandbox.

Today I’m writing about the aviation side of the anxiety caused by past traumas. Part II will come later.

I know my plane crash is nothing compared to the ones people die in, but it quite literally changed who I was, and who I would become. Still, I always feel the need to minimize my experience to acknowledge those who have it worse. Do you do this, too?

It’s also a common habit among victims and survivors of abuse. I was sexually assaulted by a very famous man. In that case, too, I always point out I didn’t suffer a modicum of the damage inflicted on some other women.

This week, the celebrity known as Diddy put out a non-apology “apology” after footage surfaced showing him beating a woman (I do not recommend watching this video). What she endured at the hands of Diddy/Puff Daddy/Sean Combs over years is some of the worst abuse you’ll ever hear about.

My assailant has a lot to say about that case. It’s been hard to see him loudly entering the conversation in my social media feeds and in the news when I know what he did. It’s beyond triggering. A very kind survivor/influencer DMed me on Twitter*** when I told her about what the celebrity did to me: Your trauma isn’t less significant. I wish I could believe her.

It’s Gonna Blow

The plane rumbled down the runway and gathered speed. My back pressed into the seat, the luggage above me shifted, the floor vibrated.

And then, at the moment of lift, we didn’t.

There came a great kerthunk and a roar, a whoosh, and whistling wind. It felt like the plane had taken off—or tried to—and slammed back to earth.

Instead of flying, we spun on the ground in circles at full speed, thrown like we were in an untethered tilt-a-whirl, helpless to do anything but go where the aircraft took us.

Thinking about where we might stop was terrifying. Visibility out the windows during that spin was nil. Would we hit a building and burn up? Crash into a lake and sink, with no way out? Fall off a cliff? It was like a spinning roulette wheel. How will I die today?

After what felt like a hundred spins, the plane came to a stop upside-down on the side of a hill, nose pointing to the sky, passengers sitting like astronauts so the cockpit door was above us instead of the fuselage ceiling.

We were alone in a crashed plane full of fuel, the blizzard was raging, and we were far from the small rural terminal. There were no cell phones, no rescue crews, no sirens. I remember the scream of silence when everything stopped.

It didn’t help that the captain seemed even more panicked than we were: “We’re not safe yet. You’re in danger of getting lost in the snow. Stay together!”

I remember how ridiculous that sounded to me. He wanted me to fear some flakes and a bit of frosty air while I was stuck upside-down in an aluminum tube that might or might not explode?

Let the storm swallow me. Let my legs give out running back. Just get me out of this stuffy cabin.

A giant asshole sitting behind us cracked himself up when he shouted, “She’s gonna blow!”

Someone opened the door. Amy and I helped each other out of the plane and onto the icy wing. There were no slides, no equipment, no help. I jumped off the wing and twisted my knee, but I still ran.

We hiked up the hill, slipping and plowing through the fresh powder, and at the top, we all looked back at the nose poking toward the night sky, shrouded in darkness and a veil of falling snow, like a wraith. A ghost plane. A business man (I remember a trench coat and a briefcase) was the only one carrying a camera. He snapped a bunch of photos and swore he’d send us pictures. He never did.

Back at the terminal, we lined up at the payphones and called our families. As I waited, I watched the captain, hat in hand, leaning against a wall. He was virtually catatonic. He was alone.

He repeated over and over, My career is over. My career is over. My career is over.

He glanced over at us, but we were too busy processing adrenaline and making alternate plans to worry about him. I didn’t say I told you so.

(Airline friends, is it possible the plane could’ve left the ground for a moment? )

Amy and I went to the rugby kegger and stayed at the house overnight. We told every person we met what had happened, and none of them could wrap their heads around it.

My two most vivid memories of that party were 1) a 6’ 4,” 250-lb senior following me around. I had to twist myself up to keep the nice and polite no thank-yous coming to finally get away. Women are never safe. 2) An Aerosmith song.

“Janie’s Got a Gun” was playing when we got to the party, and I loved it.

It became a transporter for me.

A blizzard has a scent, and when I hear that song I can smell the snow. I can feel the white whirl meet the dark night and envelop me. My mind plays a film as vivid as being there. I am there, any time I hear that song.

I’m 18 again, and nothing is in my control.

It’s no wonder I keep going back there involuntarily. As experts told NPR,

“The stress hormones, cortisol, norepinephrine, that are released during a terrifying trauma tend to render the experience vivid and memorable, especially the central aspect, the most meaningful aspects of the experience for the victim," says Richard McNally, a psychologist at Harvard University…

[Added another expert], "the central details [of the event] get burned into their memory and they may never forget them.”

After the crash, I developed a fresh phobia and anxiety, which I treated with cocktails at the airport bar when I turned 21. I still had to fly, so I gave in to some new superstitions: never set eyes on the pilots before takeoff (close your eyes if the cockpit door is open when boarding), never speak to them, and always keep your fingers crossed until the seatbelt sign dings.

For decades these rituals have kept me alive.

The other way I coped was to ask everyone with any aviation expertise to fix the wound for me. Not in so many words, but with interrogations.

Why do you like flying?

Why aren’t you scared?

Don’t you know something terrible could happen?

They would recite statistics like, You’re more likely to be killed driving to the airport than flying out of it.

Their data means little to me. Once you understand that planes crash on takeoff, you’re in another league. My lifetime of data was imprinted in my psyche, tattooed on my brain. I’d flown around 18 times by age 18 and had crashed once. My muscle memory told me planes crash, and when you get on one, you’re not safe.

This crash was also one of the reasons I felt the need to exorcise some old demons related to my former friend Sten Molin in the overly generous articles I wrote in 2021 that started this whole thing.

Trapped in a dad-style sedan cruising up Rt. 95 to Newport on our blind date, I peppered him with scenarios and challenges. I needed this American Airlines pilot to help bring back my love of travel when nothing else had. Flying for him was like going to the corner store.

Convince me. Fix me, I told Sten. He didn’t; there was nothing about my issues that he could relate to.

I have a phobia about flying. I hate everything about it.

The odds are in your favor. You’ve already had yours. You’re good for the rest of your life.

I don’t think it works like that. It could still happen.

Flying is amazing. It’s the safest way to travel.

No, it’s not. Aren’t you scared?

Scared? (Dismissive chuckling) No. I love my job. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. There’s nothing to be afraid of.

The event of him dying in a horrific crash that took the lives of 264 other people a few years later made my anxiety worse. What were the odds?

See? I was right. I told you so.

Like so many of us who remember American Airlines Flight 587, I felt less safe after that.

Last weekend I joined a newspaper subscription service that dug up old clippings, and I scoured the NTSB website.

I learned:

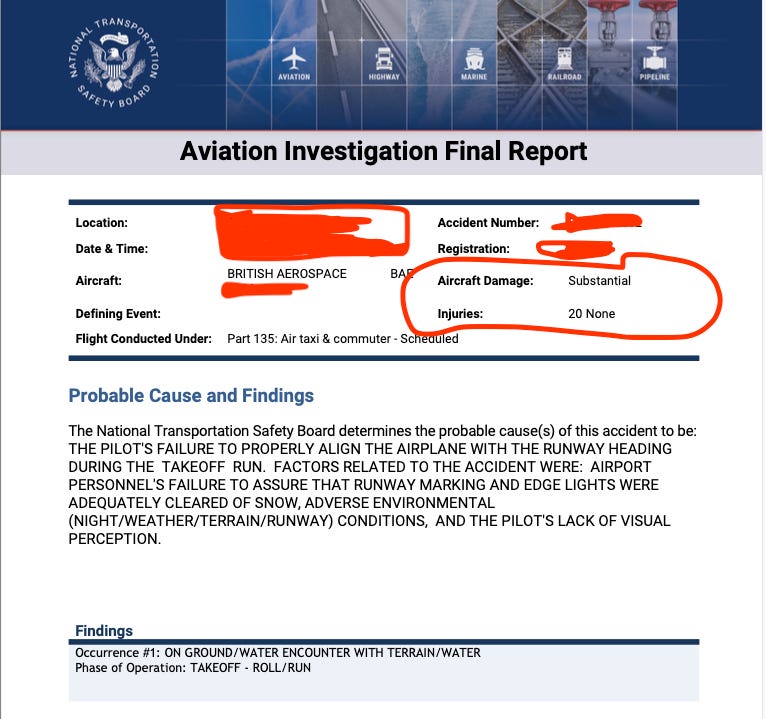

The small plane I’d thought of as a 50-seater was a British Aerospace Jetstream 31 carrying 18 passengers and 2 crew

That the pilot was blamed (mostly) for the crash, in part for “failure to properly align the airplane with the runway heading during the takeoff run”

Apparently there was water at the bottom of the hill we’d careened down. I don’t remember understanding that we’d hit water, because if I had, I’d have been a thousand times more panicked

That the news articles got a lot wrong, including the “no injuries” part; that we “blew” off the runway; and the claim there was only a little damage. The NTSB report said there was “substantial” damage to the aircraft.

We were lucky, I know that.

But the fact we could’ve died is enough to mess with anyone. The key that unlocks every bad thing is “out of control.” The plane was out of control. What happened to it was out of my control. At 18, I suffered the loss of believing for just a little while longer that I was safe.

I know a lot of you have endured past traumas that cause you anxiety to this day, and often this newsletter is a tough read—or one to avoid altogether. I know because you tell me, and because if you make it to a certain age, life will have thrown some sticky things at you. I hope you’re also subscribing to newsletters about rainbows and unicorns to balance things out.

So there you have it. Next time I’ll be writing about the sexual assault aspect of what The Landing has brought up.

xoSara

(On “the day the music died” on Feb. 3, 1959, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson were killed in their plane crash, an event immortalized in Don McLean’s 1971 hit “American Pie.”

“Investigators point to quickly-changing wintry weather conditions that were not communicated to the inexperienced pilot as the cause of the crash that left such a tragic mark on music history.”).

*I’m going to try to find Amy to see what she remembers. What details will differ? Will she remember being in the window or the aisle? Did she get hurt jumping off the wing?

**Due to incessant cyberstalking, I try to keep some details about my life private and have redacted or changed some identifying information

***I refuse to call it X

Correction: It wasn’t wake turbulence but clear air turbulence. It was during breakfast service and completely unexpected so most of the passengers were not wearing seat belts. So different scenario.

This is a great read. I am not a writer myself but I love the imagery, “shrouded in darkness and snow like a wraith”…

If brains were dynamite he wouldn’t blow his ears off. That’s not how odds work. Being involved in one serious plane crash doesn’t now mean the odds are stacked in your favour against being involved in another one.

No, he wasn’t scared of flying, but he was terrified of minor wake turbulence. A passenger in a commercial jet died this week after the plane they were flying in encountered what is believed to be severe wake turbulence. It is likely the passenger wasn’t strapped in. The pilot maintained control, (being a large heavy commercial jet the plane didn’t invert, as Molin expected Flight 587 would) and managed to land the plane, with all other passengers bruised and battered but alive.

Fear is often irrational and something you can’t reason away with statistics about safety. If you experience trauma, those memories (even small details you mention like sounds and smells) are there with you for life. It is a human survival mechanism that kept us alive as hunter gatherers. I think a psychologist rather than a pilot (especially a pilot like Molin) would be better equipped to address the issue. Commercial aviation is safe (although don’t fly on any recent Boeing) because of people like Karlene.

Any decent pilot will tell you that fear is a part of learning to fly and flying at extremes (military pilots, stunt flying, acrobatics) and we’ve all had moments of fear or doubt. But you learn from it, you improve and grow. Some pilots enjoy the adrenaline rush of pushing themselves to the limit and coming close to death.

I am so sorry about that rapper or whatever he claims to be. It seems every woman I know has a story. Every woman. Horrible and heartbreaking.